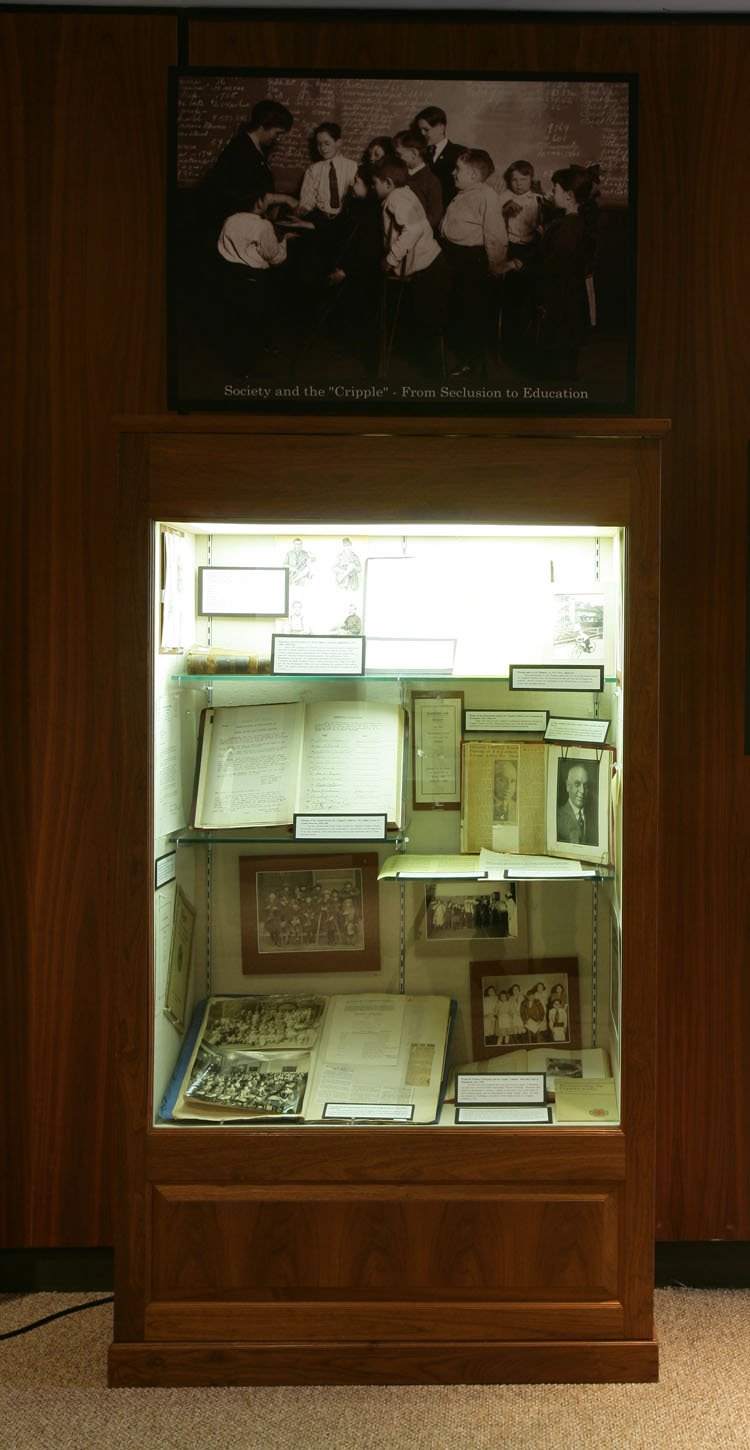

Society and the “Cripple”—From Seclusion to Education.

The 19th century saw dramatic changes in the way society treated those with physical disabilities. For the first half of the century, they were secluded in their homes because their families bore a social and moral stigma as a result of their disabilities. It was believed that parents’ improper behavior was why a child might be born with deformities. Of course, not all physical disabilities were birth defects. An increasingly industrialized economy produced dangerous working conditions in factories that maimed adults and children alike.

The Civil War forced society to confront its treatment of the disabled. Disabled war veterans were heroes, and locking them away denied their valor and the country’s sacrifice. The Progressive Era also helped, producing social activists who sought to improve the conditions of the lower classes, especially disabled people who were unable to compete in an industrialized economy. In the 1890s, many philanthropic organizations began to help the disabled by creating institutions they believed would improve their lives. A primary focus was on vocational rehabilitation. Work was a fundamental right of every member of society, and Progressives believed that finding a job made a person’s disability unimportant.

The Progressives also took an interest in disabled children. They believed that if a disabled child was cared for from the earliest age, it could become a model of improvement. He or she could be made self-reliant and no longer be a drain on society or an embarrassment. Northwest Ohio played a key role in developing services for disabled children. In 1907, a street car accident in Elyria killed the son of businessman Edgar Allen. Allen undertook a fundraising campaign to build a hospital in the town, and also discovered that Lorain County had over 200 physically disabled children who were receiving no care. He raised money to build the W. N. Gates Hospital for Sick, Crippled, and Deformed Children, which opened in 1919. Allen, a member of the Elyria Rotary, wanted to spread his mission of helping disabled children to others, so be began contacting Ohio Rotary clubs to ask for assistance.

But even before Allen began to organize a “crippled children’s movement” in Ohio, the Toledo Rotary was already assisting disabled children. In 1915, the Rotary contacted the District Nurse Association and found that disabled children were largely neglected in Toledo. In 1916, the Rotary began providing financial assistance, and under the guidance of Rotary President Charles Feilbach, they founded the Toledo Crippled Children’s School in 1918. The Toledo Society for Crippled Children, consisting largely of Rotary Club members, was established in 1920 and continued to take an active role in the care and education of disabled children. In 1924, the Crippled Children’s School was renamed the Charles Feilbach School in honor of the former Rotary president. In 1930, a new Feilbach School was built just off Cherry Street. The Feilbach School operated in this building until 1976, when it moved to a new location on Glendale Avenue in south Toledo. That school, the Glendale-Feilbach School, was built to be fully accessible to disabled children.